Institut de Biologia Evolutiva - CSIC UPF

The clay of life

Clay has always been with us. It was part of our homes in caves, shaped alongside the environment, and its craftsmanship evolved with our imagination over the centuries, across the world.

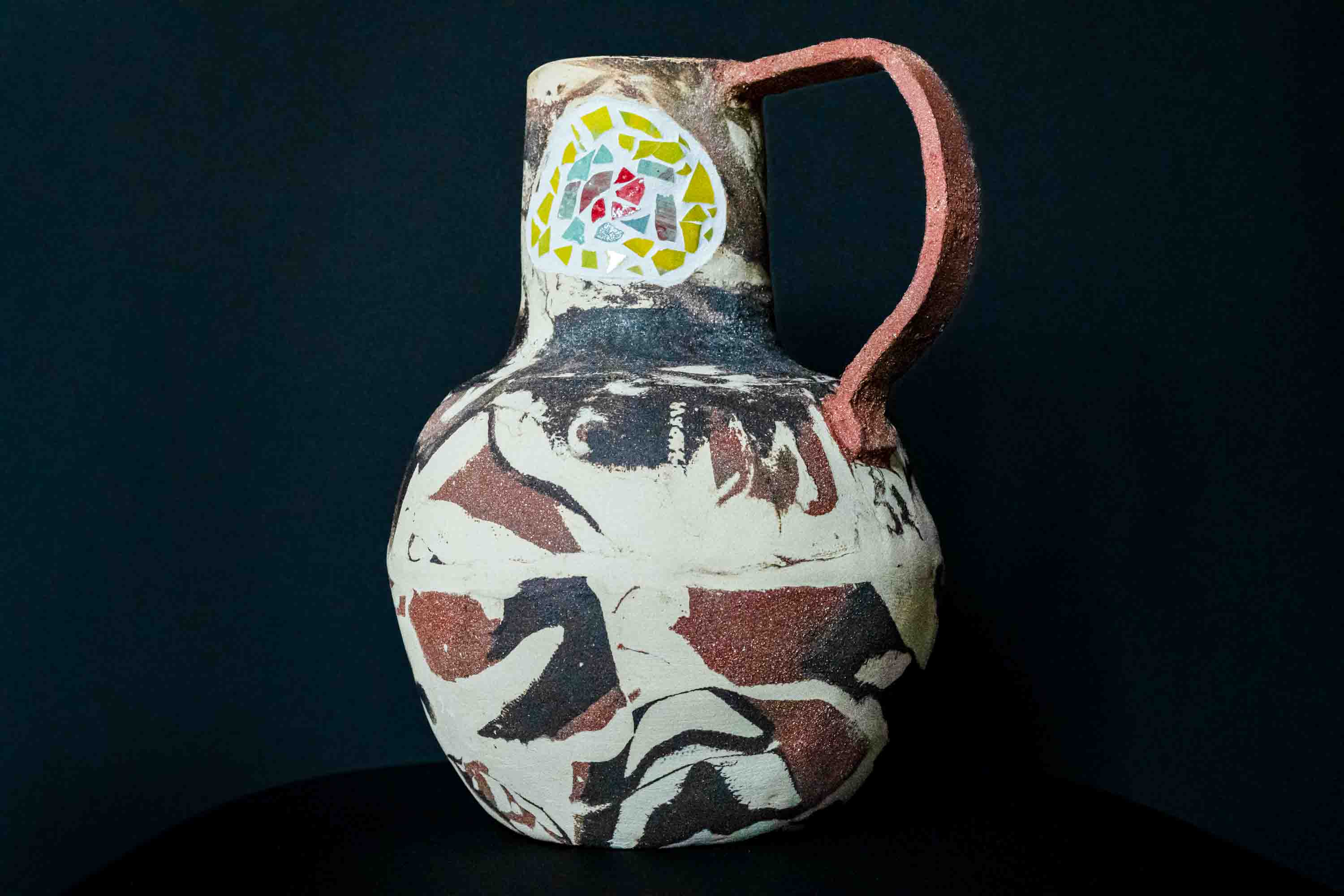

On the occasion of the International Day of Persons with Disabilities, December 3, the Diversity Committee of the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE: CSIC-UPF) has created a clay jug that symbolizes tradition, care, and cultural evolution. Today, we speak with the IBE research team (CSIC-UPF) to uncover the evolutionary ties we share with this craft.

The first hands to shape clay

To understand the origins of clay craftsmanship, we spoke with Vanessa Villalba, principal investigator of the Archaeogenomics group at the IBE. Her work combines genomics and archaeology to decipher the past of human beings. In this field, artifacts from archaeological sites are especially significant.

“Clay engravings from the Paleolithic show that symbolism, ritual, and creativity were already part of those prehistoric societies,” says Vanessa Villalba, principal investigator at the IBE.

“In archaeogenomics, we try to see whether cultural changes that occur throughout human history correlate with genetic changes resulting from migrations and mixing between past population groups.”

Regarding the people who shaped those first clays in prehistory, the researcher explains that these objects reveal both their way of life and their expressiveness. “Clay engravings from the Chauvet Cave or Paleolithic portable art show that symbolism, rituality, and creativity were already present in these societies.”

The first fired vessels appeared in the Near East, in Anatolia, among groups that had already domesticated plants and animals during the Neolithic. About two thousand years later, these techniques reached the Iberian Peninsula.

“At Neolithic sites on the peninsula, we find a mixture of two lineages: one already present before the Neolithic and another traceable back to Anatolia. This shows that not only ideas about domestication and clay craftsmanship moved, but also the people who contributed to Europe’s genetic history.”

Decorative variations on the vessels often serve as chronological markers, allowing archaeologists to date and relate different sites. It is even possible to recover molecular traces of their contents, such as evidence of ancient fermentations or dairy products.

Among the pieces found on the peninsula, the IBE researcher highlights the “Cardial” pottery, decorated with patterns made from seashells. “They are visually stunning, and thanks to archaeogenomics, we now know that the people who produced and transported these ceramics traveled across the Mediterranean about 7,000 years ago, from East to West. They are small objects, but they reveal large-scale human connections.”

Human connections are also reflected in the rituals involving these crafts. Clay vessels gained special significance in funerary contexts during the Iron Age, when the “urnfields” emerged.

“In these necropolises, the community made a vessel specifically for each deceased individual. Here, pottery becomes an object of care and remembrance, custom-made for each member of the group. This practice continued into the Roman period, especially in the case of children,” concludes Villalba.

A Transformative Technology

After its first steps in prehistory, clay craftsmanship spread and evolved across the world, with uses as diverse as the civilizations and cultures that shaped it. We spoke with Sergi Valverde, principal investigator of the Evolution of Networks Lab at the IBE, to learn how its evolution accompanied humanity.

“Ceramics evolve with us because they arise from human capacities for imitation, social learning, and cumulative memory, which themselves evolved through natural selection,” says Sergi Valverde, principal investigator at the IBE.

The researcher explains that clay craftsmanship followed models of cultural evolution. “Its expansion was very rapid because the technique was relatively easy to learn, materials were accessible to many communities, and people already mastered fire, which allowed them to produce objects reliably,” Valverde comments.

According to Valverde, the variations that appeared in this craftsmanship across different cultures result from a combination of function, available materials, cultural traditions, and aesthetic values. “Some cultures required jars with long handles for easier transport, while others opted for more compact forms because the local clay was more fragile or difficult to shape.”

Image during the creation of the IBE jar. Credit to Laura Fraile.

Tradition and aesthetics also played an important role, and sometimes the shape or decoration remained unchanged due to prestige or ritual purposes. “On some occasions, this meant that the design of clay jars remained stable for centuries, as with Greco-Roman amphorae or Longshan pottery in China, which stayed almost identical for generations.”

Taking all this into account, the cultural evolution expert describes ceramics as an evolutionary system with variation, selection, and transmission. “Culture is not something merely ‘similar’ to biology; it is an essential part of human biology. Ceramics evolve with us because they emerge from human capacities for imitation, social learning, and cumulative memory, which evolved through natural selection.”

According to experts in cultural evolution, culture is a subsystem within human evolution, an extension of evolutionary biology rather than a separate domain. This phylogenetic approach is increasingly applied in archaeology.

An example is the review article published in Biological Theory co-led by the same researcher: “Artifacts That Leave Traces: How to Build Cultural Phylogenies in Archaeology.” It shows how artisans copy, modify, and transmit techniques and designs through social learning. This generates cultural lineages that, incorporating the unique aspects of each culture, can be studied in the same way as species connected by genealogy.

The phylogenetic tree of clay vessels shows how, from an ancestral form, variants emerge exploring different solutions in proportions or neck shapes. “Some become extinct; others continue accumulating innovations. At a glance, the phylogeny reveals something that traditional typology tends to hide: material evolution is not linear but a branching process of divergence and innovation,” concludes Valverde.

An ancestral and contemporary craft

Clay craftsmanship has accompanied humanity from prehistory to the present thanks to a combination of innovation, social learning, and mobility. But what do we preserve of this ancestral technique? We spoke with the artist Laura Fraile, creator of the jar made for the IBE, a piece that unites art, design, and science.

“The nerikomi technique introduces an element of chance in the creative process. With it, I wanted to highlight genetic diversity and variability in human populations,” says Laura Fraile, artist and ceramist, and the creator of the jar and the visual identity for the IBE’s functional diversity campaign.

To make it, Fraile hand-shaped the piece using the coil-building method and combined this with slab techniques to achieve the characteristic nerikomi effect, where different colors or types of clay are mixed. “This technique introduces an element of chance in the creative process. With it, I wanted to highlight genetic diversity and variability in human populations.”

The form of the jar is inspired by Bell Beaker pottery from the Chalcolithic Mediterranean, while the handle incorporates accessibility criteria, inspired by vessels adapted for people with functional diversity. To connect the piece to Barcelona, the artist employed Gaudí-style trencadís, reflecting how fragmented elements can be integrated into a larger whole, much like mutations contribute to human evolution.

For Fraile, working with clay remains a practice that connects us with experimentation, patience, and mutual care. An ancestral craft that, thousands of years later, continues to be a space for expression and community care.

Supported by the DEEP-MaX project of the CSIC to promote scientific excellence.