Institut de Biologia Evolutiva - CSIC UPF

The first fluorescently modified cockroach could shed light on the future of insect research

Genetic editing techniques based on CRISPR/Cas9 have revolutionized biotechnological research over the past decade, as they enable genes to be “cut and pasted” with high precision in a wide range of organisms. However, their application in non-model insects such as B. germanica has so far faced significant technical limitations.

Now, a team of the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE), a joint centre of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and the Pompeu Fabra University (UPF), has for the first time inserted a stable and heritable gene into embryos of B. germanica using a new molecular tool based on DIPA-CRISPR. This breakthrough could shed light on the biological, genetic, and evolutionary processes of these insects, which are highly relevant both for evolutionary studies and for pest control.

A new molecular tool that facilitates research in non-model insects

Genetic manipulation of embryos has been crucial for studying the development of many species, but some insects lay eggs that are difficult to manipulate due to their hard, fragile, or inaccessible coverings. To overcome these obstacles, in 2022 the IBE team participated in the development of DIPA-CRISPR, the first genetic editing technique capable of inactivating genes (knock-out) in cockroach embryos by injecting CRISPR “genetic scissors” into the abdomen of the mother, making these changes heritable.

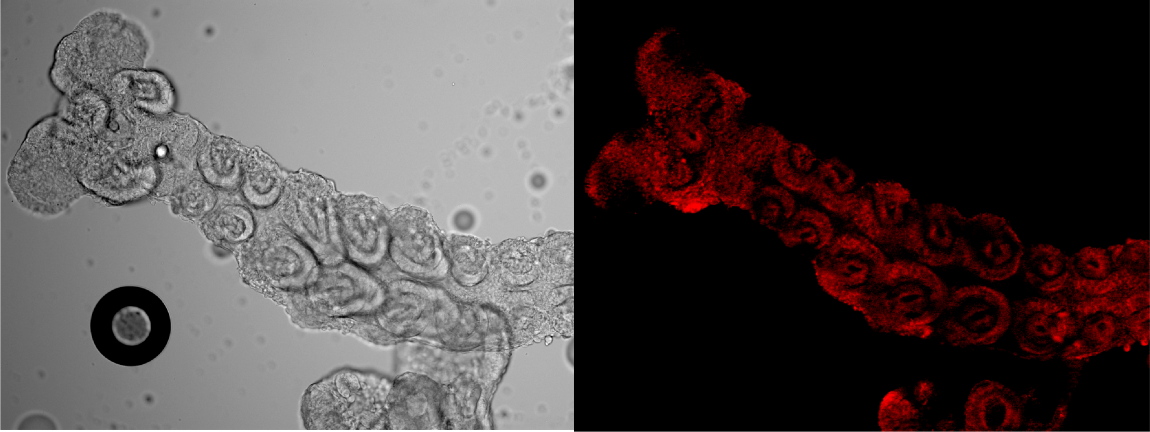

The protein expressed by the distal-less (dll) gene accumulates in the appendages and nervous system during embryonic development. The red mCherry signal reveals the location of the Dll protein in developing appendages and in the embryonic nervous system. Nuclei stained with DAPI (blue) allow visualization of tissue organization. The images show that the fusion protein is functional and illustrate its localization during cockroach development. Credit: Alfonso Ferrández-Roldán / Cell Reports Methods.

This new research, published in Cell Reports Methods, takes a step further with the first genetic insertion (knock-in) in embryos of Blattella germanica. Using a CRISPR-based strategy, the team was able to “cut” a gene essential for embryonic development (distal-less) and fuse it with a red fluorescent protein gene (mCherry), using homology-directed repair. The insertion was successful in approximately 30% of the injected females, producing embryos with detectable fluorescence, and it is both stable and heritable.

“We have developed a new molecular tool that is simple, robust, and cost-effective, which, unlike other methods, does not require complex modifications or specialized equipment. This opens the door to generating fusion proteins in non-model insects,” says Maria Dolors Piulachs, principal investigator of the Insect Reproduction Group at the IBE, who led the study.

Locating proteins in the dark: a key advance in cockroach research

By inserting fluorescence into distal-less, the study has enabled live, real-time visualization of the Dll protein expressed by this gene in developing appendages and in the nervous system of B. germanica during the embryonic stage. Importantly, the fluorescent protein produced is functional and does not interfere with the normal development of the insect — a milestone that paves the way for future research.

Protein tagging using DIPA-CRISPR: graphical representation of the process of injecting the gene-editing machinery into an adult female German cockroach to insert the mCherry fluorescent protein gene (knock-in) at a location that allows visualization of the protein expressed by the distal-less (dll) gene during embryo development. Credit: Alfonso Ferrández-Roldán / Cell Reports Methods.

“We have confirmed the distribution of a protein that is key to the development of many insects. Thanks to this new tool, we expect to be able to study the expression of different cockroach proteins without needing fluorescent antibodies — a resource that is often unavailable or very difficult to obtain in non-model insects, and considerably more expensive,” says Alfonso Ferrández-Roldán, Juan de la Cierva postdoctoral researcher at the IBE and first author of the study. He adds: “We will now be able to resolve and explore developmental mechanisms in this species, which is of sanitary and economic interest, but also of evolutionary importance.”

The German cockroach (B. germanica) is of particular scientific interest, both because of its relevance as a pest and due to its basal evolutionary position, which helps deepen our understanding of insect evolution. Research on its reproduction could also contribute to the development of new pest control strategies.

“In the future, this technique could be applied to other non-model insects and enable the simultaneous study of multiple genes using different fluorescent markers,” Piulachs concludes.

Referenced article:

A. Ferrández-Roldán and M.-D. Piulachs, “Using DIPA-CRISPR for simple and efficient endogenous protein tagging in insects” (2026). Cell Reports Methods.